Uber Eats: introduction

/So far I’ve been writing about my experiences working for DoorDash, for the simple reason that my old phone didn’t support the Uber Driver app. That phone finally reached the end of its useful lifespan, and I finally replaced it, which meant I was ready to start experimenting with Uber Eats. Today I’ll share my overall impressions, and go into more detail about individual features in future posts.

Signing up

Just as with DoorDash, signing up to work for Uber was so simple I didn’t bother taking screenshots. Since I was only signing up to deliver using bikes and scooters, the only part of the process that took any time at all was the background check, which came through in a few minutes.

I suspect the process can be more time-consuming if you are signing up to deliver using a car or to deliver people instead of food, since I assume they check your license, registration, and insurance coverage as well. If they find anything on your background check you may have more difficulty getting on the platform as well, but I don’t know how strict Uber is about that kind of thing.

The Uber Driver interface is baffling, but you don’t use it for anything

I’ve always found that the customer-facing Uber app works pretty well, or at least the way you would expect it to work: you enter your origin and your destination and it gives you some prices and options, you click one, then you pay with a card you have on file.

The Uber Driver app isn’t like that at all. In fact, it’s almost ludicrously primitive. There are basically only three buttons that do anything: a button that says “GO,” a button that says “STOP,” and a little icon in the shape of a coffee cup which lets you pause orders.

There are a few more things you can can do buried in the app’s menus, like set up your direct deposit, but not much. Frankly, as a driver I was expecting a bit more of a peak behind the curtain, but that’s about it.

Uber hides tips

Here I owe an apology to Kellen Browning, the author of the New York Times story I referenced in May. I genuinely did not realize just how weird Uber is about the tip portion of their workers’ pay.

Like DoorDash, Uber will show you an upfront amount including what they call an “expected” tip. This is manifestly absurd. The tip has already been included in the order, it’s already been processed by the credit card company, there is nothing “expected” about the tip — it has already been paid in the past by the time you see an order.

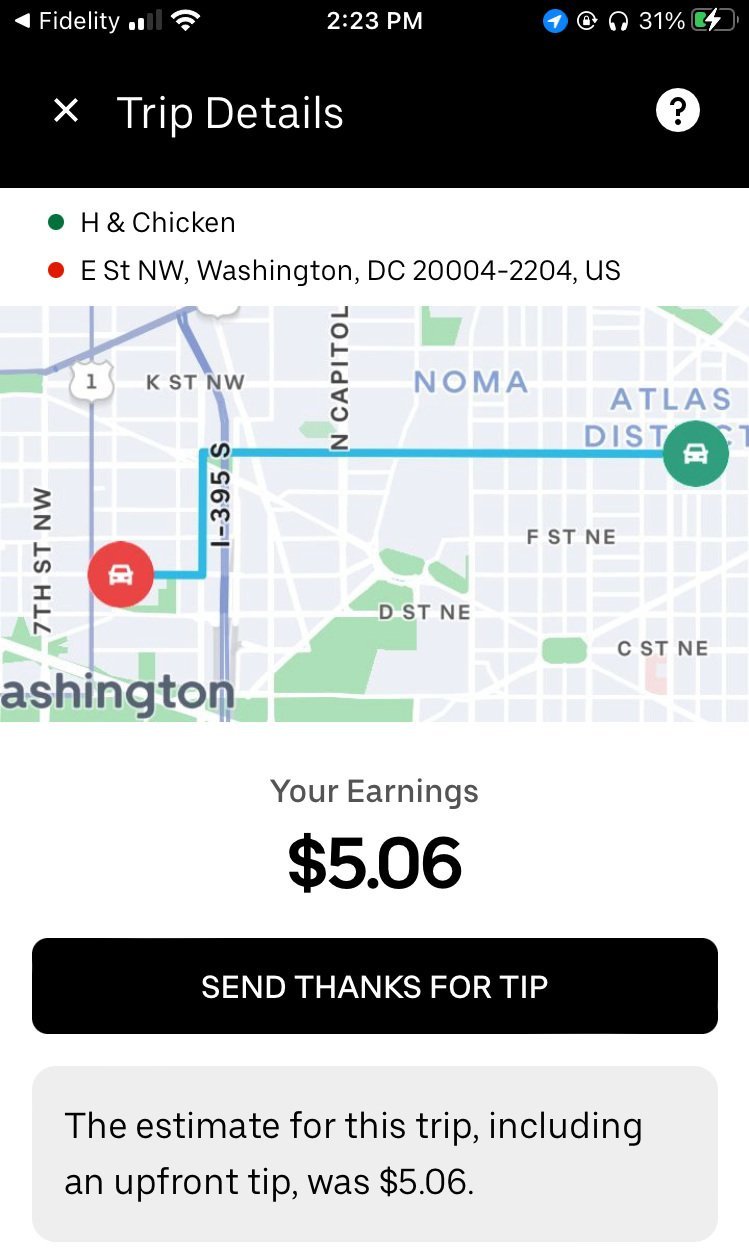

What Uber actually means is they will not tell you how much you have actually earned on an order until “roughly” an hour after the order has been completed. Here’s what that looks like in the app, when you complete an order and after the tip is revealed:

The thing to pay attention to here is not the “estimated” trip amount (a fiction), but the timestamps. I did not know how much this order would actually pay until 100 minutes after I had already dropped off the food — the order was delivered at 12:43 pm and the pay wasn’t finalized until 2:23 pm!

Uber gets a lot of orders

Working for DoorDash has a lot of periodic frustrations (like customers), but if there’s one word I would use to describe the experience, it would be “leisurely.” During a typical lunch shift, I can get about 3 or 4 orders per hour, each of which takes “about” 15 minutes and pays “somewhere between” $6 and $12. These are just convenient round numbers I tell friends and family, obviously the actual amounts vary daily, more or less at random. I usually work for DoorDash when I’m running other errands, and when an attractive order comes in, I can take it and then get back to my own stuff until I get another order.

Uber, in my experience, is nothing like that. From the second I press the app’s “GO” button, a firehose of orders starts streaming out. It is frankly impossible to do anything or even think about anything else while the app sends push notifications, sound effects, and every other kind of nightmare our devices are capable of producing.

If that sounds like a feature (and for some people I assume it is), the problem is the orders make no sense.

Uber forces you to be a lot pickier than DoorDash

Virtually every DoorDash order I get makes instant sense: it’s usually a merchant relatively close to my current location and a customer 5-10 minutes away at 10 miles per hour. Since DoorDash shows you how much the order will pay, including tips (up to a certain amount), it’s easy to apply a simple rule like needing $5 per mile in order to accept an order.

Uber will happily send me to a McDonalds 3 miles across town, then backtrack past 3 other McDonalds to a customer on the other side of town. If you’re not paying attention, you can accept an order like that and spend an hour ferrying around a cold $9 cheeseburger. If the pay were high enough, that might still be an order worth taking. The problem is, since Uber conceals tips, there’s no way of knowing whether the pay is high enough.

Uber has a trust problem

I think if you loaded an Uber engineer up on sodium pentothal and asked why the app issues these bizarre orders, they would tell you something like this:

“Since Uber has access to the history of every order placed on the platform in every conceivable set of conditions, we are uniquely capable of optimally distributing every order — including orders that have not yet been placed! — across the entire pool of drivers so that customer satisfaction is maximized and driver pay is as fair as possible. However, since Uber can only assign orders that have already been placed, we can’t tell you to go to a specific restaurant where we expect a future order to be placed. Instead, we use orders that have been placed to move drivers into position for those future, more reasonable orders. All you have to do is trust us.”

Besides having absolutely no faith that Uber engineers are capable of executing this task, there is an additional problem: for the system to work as described, drivers have to trust not just in the talent and ingenuity of Uber’s engineers, but also that Uber is acting in their best interests. In fact, of course, nobody trusts Uber because Uber does not behave in a trustworthy way.

On the contrary, from its very inception and at every junction since, Uber has behaved like a sociopath. It operated or operates illegally in virtually every market it enters. When its lawbreaking is discovered, it pretends to be the victim. When laws are passed to create regulatory frameworks it disapproves of, it dumps vast amounts of investor money into overturning them. When customers are assaulted, it demands silence when it compensates its victims so the public only learns about a fraction of them (while investors are compensated for the hit to Uber’s share price).

And then they ask workers to “trust” them?

Uber seems totally indifferent to performance

Another interesting difference between working for DoorDash and for Uber is that DoorDash puts a priority on high performance. For example, drivers with a high acceptance rate are given priority for what DoorDash calls “high-paying orders;” virtually all my orders are now classified as “high-paying” (don’t get too excited, that just means $6 instead of $3 most of the time).

Likewise, DoorDash gives you a timeframe they expect you to pick up and deliver orders in. As I’ve mentioned before, these timeframes are extremely generous (I have a 98% on-time rate and I’m literally puttering around on scooters at 10 miles per hour), but they are there, and if DoorDash detects you’re going the wrong direction or not moving towards your destination they can and will cancel the order and assign a different worker. If DoorDash detects you’ve gone offline or your device isn’t responding, they’ll automatically pause your dash (this is actually a feature in my experience since it means your acceptance rate doesn’t crash if you hit a dead spot).

Uber isn’t like that. As far I can tell, Uber basically doesn’t care how you use the platform. There is one nuance, “Uber Eats Pro,” which is trivially easy to qualify for, but it also doesn’t have any real benefits unless you want to take classes through ASU Online, which also requires 2,000 lifetime deliveries before you qualify.

Other than that, Uber just doesn’t seem to care about anything. There’s no incentive for fast delivery other than being able to make more deliveries. There’s no punishment for having a low acceptance rate or even for canceling orders. This is good because the app is so bad that I frequently have to cancel orders when I realize exactly where Uber wants me to go.

This also helps explain the at-first-baffling remark in the Browning article that workers will reject “scores of low-value orders while waiting for hours for a big get from a high-end restaurant.” On DoorDash that strategy will actively reduce your likelihood of receiving a high-paying order, while on Uber it is absolutely essential to reject orders in order to make enough money to leave the house. Consequently, my acceptance rate on DoorDash is currently 74% (I accept also every order I receive) and on Uber it is just 22% (I turn down almost every order I receive).

Uber sells drivers

While DoorDash does sell literally sell stuff to drivers (those red bags aren’t always free!), and has a few marketing offers for things like a debit card to receive instant payouts, Uber is much more aggressive in selling every part of its workers. Of course they sell their workers’ labor power, the social capital that goes along with it, and the value of their vehicle and fuel. But beyond that they also sell access to drivers as customers.

Think of Uber as a giant affiliate marketing engine, like a credit card review website. On a website, readers are attracted by useful, entertaining, or accurate information. Then their attention is sold on to banks, or mattress companies, or food box delivery services.

In Uber’s case, workers are attracted onto the platform with literal money: the payments workers receive for deliveries. Then once Uber has their attention, it’s sold onwards to companies in exactly the same way.

I receive 2-3 e-mails per day with affiliate offers, all from Uber. Since Uber knows workers will worry about any e-mail from their boss, the open rate on those e-mails must be among the highest of any affiliate advertising in history. Within the app there are ads for discounts at restaurants and gas stations, who know they have to pay to be included since they don’t want to be the only ones not listed.

You can call me naive, but after my experience with DoorDash I genuinely was not expecting this level of constant marketing bombardment. Why would a company allow its advertisers to be so aggressive that at the margin it hounds its own workers off the platform? Of course, upon a moment’s reflection, the explanation is obvious. Uber loses money offering services that people want to buy, and it always will. But if you think of the difference between the money Uber receives from retail customers and that it pays out to drivers and restaurants as an audience acquisition cost, then there’s nothing left to explain: the affiliate relationship division is the only floor of the building that makes any money!

Now, will it make enough money to survive sustained 6% interest rates? I doubt it. But without that beacon of revenue the investors would be getting even more impatient at the loud sucking sound coming from the rest of the company.