So far I’ve only written about my experience working for DoorDash and Uber Eats for the simple reason that it took me a surprisingly long time to get approved to work for Grubhub. Since I did finally get hired and begin delivering for Grubhub, this post will give an introduction to that platform and familiarize you with the basics of how it works. I apologize in advance that this is a bit of an information dump, but there’s a lot of ground to cover.

Signing up: the waitlist

When I was writing about signing up for DoorDash and Uber Eats it was a bit hard to find anything memorable to say. You upload some identifying information, a headshot, and your government ID, and you can start working within 15-20 minutes. Grubhub isn’t like that, at least in my area, for the simple reason that in many markets Grubhub puts applicants on a waitlist.

If you have any interest in working for Grubhub, or if you’re even vaguely (or intensely!) curious how these platforms work in the real world, download the “GH Drivers” smartphone app and enter your information right now. It won’t take long and this post will be here when you get back.

All set? Let’s continue.

I initially signed up to the waitlist in February, 2023. Every month after that, I was informed that my application was “about to time out” and to click on a button in the app to “renew” my application.

In June, I was twice informed by text and e-mail that “my market was hiring.” Despite immediately clicking through the provided links, by the time the page loaded the market was already “closed.”

Finally (after “renewing” my application again in July and August, 2023), I managed to make it to the actual application process.

Signing up: the application

Once you’ve managed to get off the waitlist and into the actual employment application, it resembles in many ways that of DoorDash and Uber Eats. Don’t be fooled.

I signed up to work for Grubhub with scooters, bikes, and e-bikes, just as I have with DoorDash and Uber Eats. These vehicles do not require motor vehicle licenses in my jurisdiction (although I do have one). So when I was asked to upload my government ID to the Grubhub app, I uploaded a picture of my US passport.

This was an error.

The same day, I received an e-mail from Grubhub saying:

“Thank you for your interest in delivering with Grubhub! Unfortunately, we are unable to continue with your application, as the document provided does not meet our requirements for car/motorcycle/scooter deliveries.”

That was it. That e-mail address has been permanently, as far as I can tell, burned with Grubhub. I never received any reply to any of my e-mails providing additional evidence of my fitness for work.

Obviously, it was no trouble signing up again with another one of my throwaway e-mail addresses, although I did have to create another Google Voice number since the number I used for my first application could not be used again. A month later, I got another e-mail notifying me it was time to apply again.

This time, understanding how finicky the system is, I uploaded pristine pictures of my drivers license on a perfectly squared black background with plenty of lighting and contrast, and within 24 hours I was deemed eligible to work.

Don’t touch anything: Grubhub is very sensitive

There are four major elements of working for Grubhub you need to know before you touch anything in the app. I tell you this not so you won’t make the mistakes I made, but so that you understand the mistakes you might make faster than I did.

The “STATUS” toggle

What DoorDash calls the “Dash Now” button and Uber Eats calls the “GO” button is called the “Status” toggle in Grubhub. You can slide the toggle from “unavailable” to “available” when you want to receive orders. You can also slide the toggle back to “unavailable” during a delivery if you don’t want to receive any more orders, just like on the other apps.

If you’re already confident multi-wielding, then you could use Grubhub as a second or third tool in your kit and just toggle on and off as orders come in on your various apps.

Frankly, that’s how I plan on using it, if I ever feel inclined to use it at all in the future. However, like the other platforms, Grubhub has a complicated series of incentives designed to influence how you use the app.

Grubhub’s performance metrics

Once your account is set up, you’ll see four icons on the bottom of the screen. The one on the far right is labeled “Account,” where you can click the “View my stats” button and see your current performance metrics: “Offer committment,” “On-time arrival at merchant,” and “Schedule commitment.”

The first big difference here between Grubhub and my other two platforms is that Grubhub measures your performance on a rolling 14-day basis. Every day, the earliest day’s performance rolls out of each metric, whether or not you delivered on either day. This is in contrast to DoorDash and Uber Eats, which use a rolling 100-delivery basis. In other words, while each DoorDash and Uber Eats order is “sticky,” only being eliminated from your average after you complete another 100 deliveries, Grubhub’s are exactly the opposite. If you have a bad day on Grubhub, just put down the app for 2 weeks and all your late deliveries and missed shifts are washed away like tears in the rain.

“Offer commitment” is a combination of two metrics in the other apps, measuring both your acceptance rate and your completion rate. An order only counts towards offer commitment if you both accept it and you complete the delivery. This is a huge problem if you’re trying to game Grubhub’s incentives. In all three apps, you are not told the contents of an order until you accept it. This matters because orders from the same merchant can have totally different requirements. The example that illustrates this best is the pizza places that dot our urban landscapes: there’s no way to know whether any given order is for four extra large pizzas or a chicken parmesan sandwich. One order easily fits on an e-bike, the other doesn’t stand a chance. When I’m working for DoorDash or Uber Eats, I can accept those orders and quickly cancel if the order proves too large, keeping my high acceptance rate and taking only a tiny hit to my completion rate.

“On-time arrival at merchant,” is a black box. When you accept an order, the app gives you an “arrive by” time. According to the app “The closer your arrival time is to the ‘arrive by’ time on your map, the higher this stat will be.” Grubhub does not disclose how that “arrive by” time is calculated or how your actual arrival affects this performance metric. This is obviously another huge problem if you’re trying to game Grubhub’s performance metrics.

Finally, “Schedule commitment” is a completely unique Grubhub metric, since Grubhub relies on scheduling in a totally different way from the other apps, which I’ll explain shortly. This metric is calculated based on the total number of shifts you schedule, and I think is calculated more or less down to the minute, e.g., if you have scheduled one, one-hour shift and are available for 55 minutes of it your “schedule commitment” will be 92%.

Each of the metrics has a different performance threshold you need to meet to acquire Grubhub elite status (about which more below). While Grubhub calculates each performance metric roughly hourly so you can see how you’re doing, the metrics only actually matter once a week, on Mondays at 10:00 am, when Grubhub takes a final snapshot of all your metrics and awards you a status level, which will last until the next Monday.

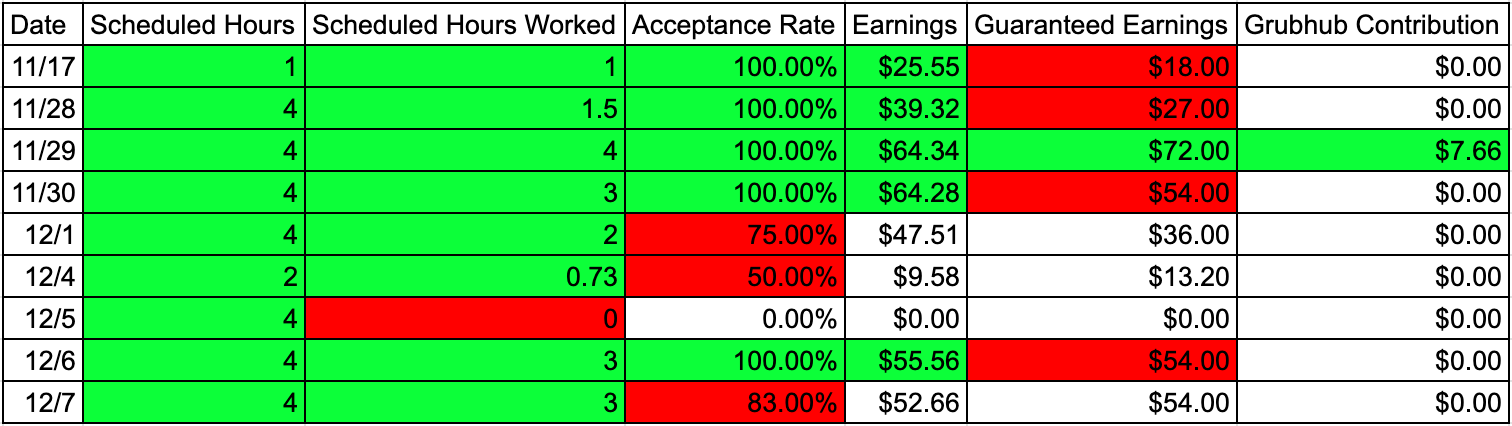

The Grubhub Contribution

I had to get all that out of the way in order to talk about the main feature that distinguishes Grubhub from DoorDash and Uber Eats: the Grubhub Contribution. Under certain circumstances, Grubhub will top up your income so that you earn a specified amount for each scheduled shift you work.

As you’d expect, the rules around this are extremely complicated, so I’ll try to spell them out as clearly as possible. Here are the three basic principles to keep in mind:

The Grubhub Contribution is determined on a daily, not hourly, weekly or monthly basis.

To receive the Grubhub Contribution you must work a scheduled shift.

And on the day of the scheduled shift you must accept 90% of the offers you receive.

If you accept 90% of your offers on a given day, and work a scheduled shift on that day, then if your total pay for the entire day is less than the specified amount per scheduled hour you worked, Grubhub will make up the difference.

You can find the rate that Grubhub will top up your income to in the app by going to “Account,” “Help,” and “Payments,” or by searching reddit for a datapoint from your area. In my area the amount is $18 per hour, a dollar more than our local minimum wage.

Hacking the Grubhub Contribution

In striking evidence of how much work people will do to avoid working, lots of people have posted about trying to game the Grubhub contribution in order to get paid without having to actually, you know, drive around delivering food to people. It is possible, it is difficult, and it doesn’t cost anything to try.

To understand why it’s so hard to trigger the Grubhub Contribution, let alone game it, we need to dive deeper into each of the requirements.

First, you need to work a scheduled shift. Unlike DoorDash, where scheduling is a way to “reserve” a slot ahead of time in case they cap the number of active workers, Grubhub takes scheduling very seriously. Hour-long shifts, which Grubhub calls “blocks", are made available for scheduling one day a week, depending on your status level. “Premier” workers get access to blocks first and can set their availability in advance so they automatically request their most desired blocks. “Pro” workers get access a day or two after that, and “Partner” workers get access last. I’m being vague because like the Grubhub Contribution, I believe the schedule release dates may also vary by market, but as a Partner worker I get access to the schedule at 10:30 am on Saturdays for shifts beginning at 6:00 am the next Monday.

By the time the schedule opens to Partners, there may not be many shifts remaining. Grubhub does have a 24-hour schedule so if you really want to experiment with scheduling you can find shifts most days around 2 or 3 am.

The next hurdle is the acceptance rate. To be eligible for a Grubhub Contribution on a given day, you have to have a 90% acceptance rate on that day (not just during your scheduled shift). If you get 10 orders during a day, you can only turn down one of them. If you get less than 10 orders during the day, you have to accept them all. Keep in mind that Grubhub is under no obligation to play fair. If you’re in danger of triggering a Grubhub Contribution, they can send you the most ridiculous orders in their system, knowing you only need to decline one to lose the money.

If you manage to schedule a shift, work it, and accept 90% of the orders you receive on that day, then congratulations, you’re eligible for a Grubhub Contribution. I say you’re eligible for it, not that you’re receiving it, because to actually receive a Grubhub Contribution you have to meet the final test: your total income for the day must be less than your market’s minimum for each scheduled shift you worked.

Simply put, the most common way to lose a Grubhub Contribution is to earn too much money that day. Let me give a few examples of how this can happen.

First, you may earn too much during your scheduled shifts. If I schedule and work a one-hour shift, and I earn $20 during that shift, I’m not entitled to a Grubhub Contribution because my total earning for the day exceeded $18 per scheduled shift.

Second, you may lose your Grubhub Contribution by earning too much during unscheduled shifts. If I work a scheduled morning shift and receive no orders, I’m entitled to $18. If I become available for an hour that evening and earn $18, I’m no longer entitled to a Grubhub Contribution because I already earned $18 per scheduled shift.

These examples illustrate the main rule of gaming the Grubhub Contribution: on a day you are trying to trigger a Grubhub Contribution, do not work any unscheduled time until you have already exceeded your market’s minimum. Once you’ve exceeded the minimum, or become ineligible by declining an order, then you can feel free to work as much unscheduled time as you please.

The status casino

Seriously gaming the Grubhub Contribution involves playing a kind of status video poker: if you’re very, very good, you can maximize your odds, but it’s still a game of chance.

In order to get access to the shifts you think have the best odds of triggering the Grubhub Contribution, you need early access to the schedule. To get early access to the schedule, you need Premier status. And to get Premier status, you need a 95% offer commitment rate, 80% on-time arrival at merchant rate, and 95% schedule committment rate.

Offer commitment is the metric most in your control, since you can simply accept and complete one order to achieve a 100% offer commitment rate. On-time arrival at merchant is harder to control since you don’t know how Grubhub will calculate your expected arrival time. If you’re late according to their calculation, you need to accept and complete more orders to have a chance to drag that score back up. The difficulty of schedule commitment depends on how many slots are still available by the time the schedule opens to you.

If you’re able to hit all three Premier metrics, then the following week when your status resets, you’ll have access to early scheduling for the following week. You’ll have first dibs on the shifts you think are most likely to generate a Grubhub Contribution. During that week, having to make actual deliveries in the real world will probably cause your stats to tank and your status to drop. But fortunately, two weeks after that all will be forgiven and you can start the cycle over.

Of course, you have the option of using the same tactics to become Premier and then use the platform as intended.

Grubhub is the most job-like delivery service I’ve worked for

I have been talking about how to game Grubhub’s mechanics because that’s how my brain works, but another way of looking at all these mechanics is that they are designed to replicate a normal workplace.

While DoorDash has a pretty meaningless scheduling function and Uber Eats doesn’t have one at all, Grubhub puts the schedule front and center. There’s a reason people like having jobs: they are guaranteed a certain amount of pay for a certain amount of work, and Grubhub provides that. A student scheduling shifts around classes or a parent scheduling around the schoolday could use Grubhub to earn some guaranteed income with the possibility of earning more depending on the orders they receive.

Likewise, if you have Premier status and early access to the schedule, you can make Grubhub a full-time or more-than-full-time job. In my market you could earn around $30,000 a year working 35 hours a week, which might not get you rich but is certainly a nice contribution to a household budget.

The flip side of that is what people hate about jobs: the lack of control. In order to get and keep early access to the schedule, in order to get the shifts you want, you need to pretty much do what Grubhub say, and if you don’t you face escalating consequences, just like in a normal workplace. If you turn down one order, you’re risking your guaranteed pay for the day. If you turn down two orders, you’ve almost certainly lost it. You can turn down 5 orders for every 95 you accept. Turn down a sixth and you’re busted down to Pro status, with less control over your schedule. Turn down 21 orders in 100, and you’re busted all the way back down to Partner, with the corresponding need to reset your stats and start over.

Comply and be rewarded, resist and be replaced.

Conclusion

One thing I’ve been surprised at is how I’ve come to associate each of the three apps I’ve used with a kind of “personality.” Perhaps that’s inevitable: the sheer impersonality of the apps, the repetitive prompts, the cheerful inhumanity almost forces the human imagination to find something relatable underneath.

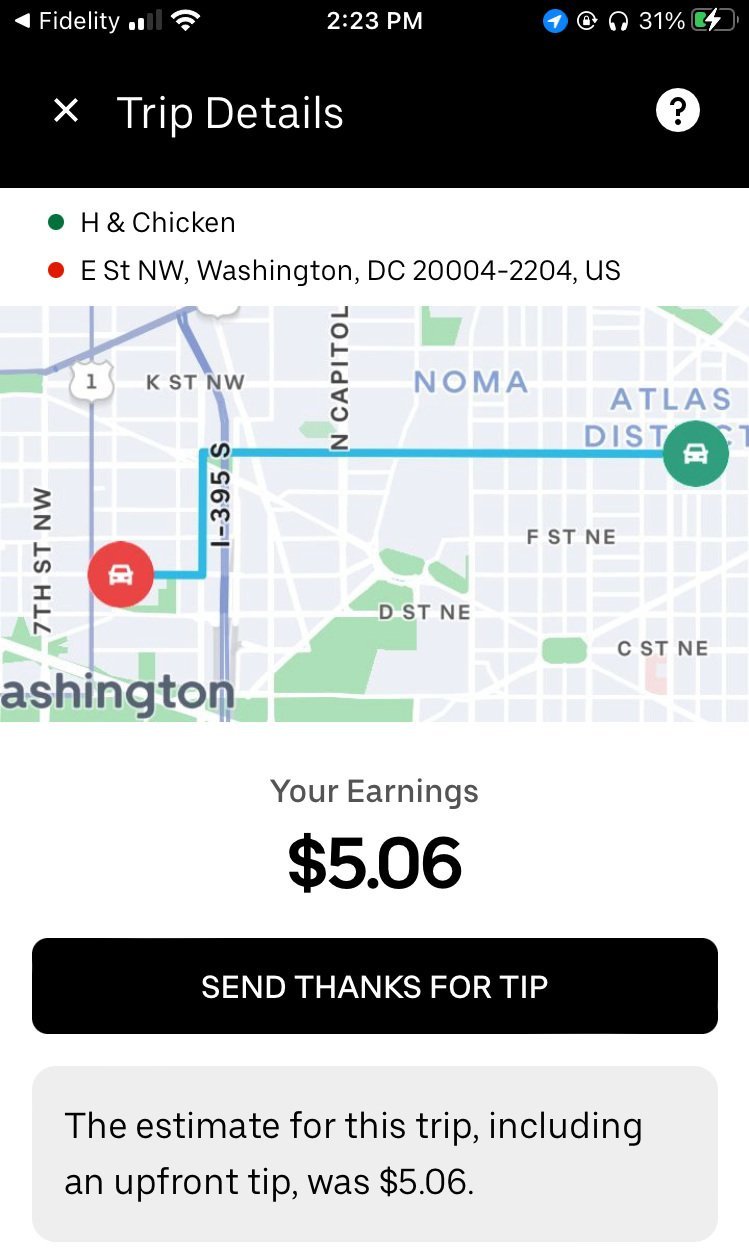

Uber Eats comes across as a kind of frenzied panic, shoving orders out the door with no rhyme or reason, just praying most of the right food gets to the right place most of the time.

DoorDash treats me with a kind of cool dispassion. They know the restaurants I like to deliver from, they know the distances I like to travel, and they know the pay I need to accept orders. Don’t get me wrong: they try to slip in the occasional Taco Bell or Popeye’s order (I hate fountain drinks), they sometimes try to send me to neighborhoods I hate biking around in, and they sometimes try to lowball me. But overall, we get along just fine.

My experience (in well under 100 orders) is that Grubhub acts like a petty Starbucks manager. All the pressure in the app is to schedule shifts in advance, work all the shifts you schedule, and accept and complete every order you’re given. If you do that, and you get lucky, then maybe you move up the pecking order until the next time you slip up. If you get unlucky the boss gives you an impossible order and you drop straight to the bottom.

These are just vibes, and are therefore mine alone. You’ll surely get different vibes from each of the apps depending on your own personality and the conditions in your market, and those conditions are also certain to change over time, especially if the long-awaited consolidation of the delivery market ever starts to take place.