Uber Eats: stacking guarantees and quests

/Back in the days of 0% interest rates and the blistering (and blisteringly illegal) expansion of app-based logistics companies, I would often read about drivers receiving bonuses in the thousands of dollars after completing a specified number of orders.

However true or common the anecdotes were, those days seem to be long gone. Even bonuses for signing up to deliver using referral links are pitiful. My personal referral link only offers $600 after completing 290 deliveries in 60 days. While that may technically be possible, it would be absolutely grueling to do on a brand new account; I’ve been delivering for about 14 months and have only completed 1,202 total deliveries. It probably took me 6 months or more to get all the way to 290.

Bonuses are still offered, however, although for much smaller amounts and over much shorter time periods, sometimes as short as a few hours. All the bonuses I’ve seen have been one of two types: “guarantees” and “quests” (or what Grubhub calls “missions”). In Uber Eats, you are also occasionally given a choice whether to aim for a higher bonus requiring more deliveries or a smaller bonus requiring fewer.

Guarantees

A guarantee is when a company offers to top up your total earnings if you earn less than a specified amount over a specified number of deliveries. If you earn more than the guarantee, then you are not paid any more, but if you earn less, then the company makes up the difference.

Quests

Quests and missions offer bonus payments on top of your earnings when you complete a certain number of deliveries. These can be one-time bonuses or repeatable payments, and they are sometimes “laddered” so you might receive $5 after completing 5 deliveries, another $10 after completely 10 deliveries, and $20 after completing 20, for a total of $35 after 20 deliveries, or $1.75 in bonus pay per order.

Stacking guarantees and quests

Two weeks ago I had the opportunity to play around with a great pair of stackable offers.

First, I was offered a $260 guarantee if I completed 40 orders, or $6.50 per order. On its own, this might get my attention, but it wouldn’t be enough to get me to work for Uber, let alone complete 40 orders, since my average earnings on Doordash are over $8 per order.

Second, I was offered a quest for $25 each time I completed 10 orders, up to four times, or $2.50 per order. Obviously, the first thing I checked was whether that $100 would count against my guaranteed earnings, and fortunately Uber Eats explicitly mentioned in the terms and conditions of the guarantee that “Earnings from your deliveries (after services fees and certain charges are deducted, such as city or local government charges), tips, and incentives (including surge and trip supplements but excluding Quest) are included toward your offer amount” [emphasis mine].

Now, after completing 40 deliveries I was guaranteed to earn $360 total, or at least $9 per order. A $9 order for me is basically always a good order, and there’s no way I would ever get forty $9 orders in a row from Uber Eats. But now, my next 40 orders were all going to be $9 orders, regardless of the base pay or tip. At one point a lady told me she’d leave me a big tip and I almost told her not to bother, since it wouldn’t affect my income at all, but I thought it might hurt her feelings if I did so I let it go.

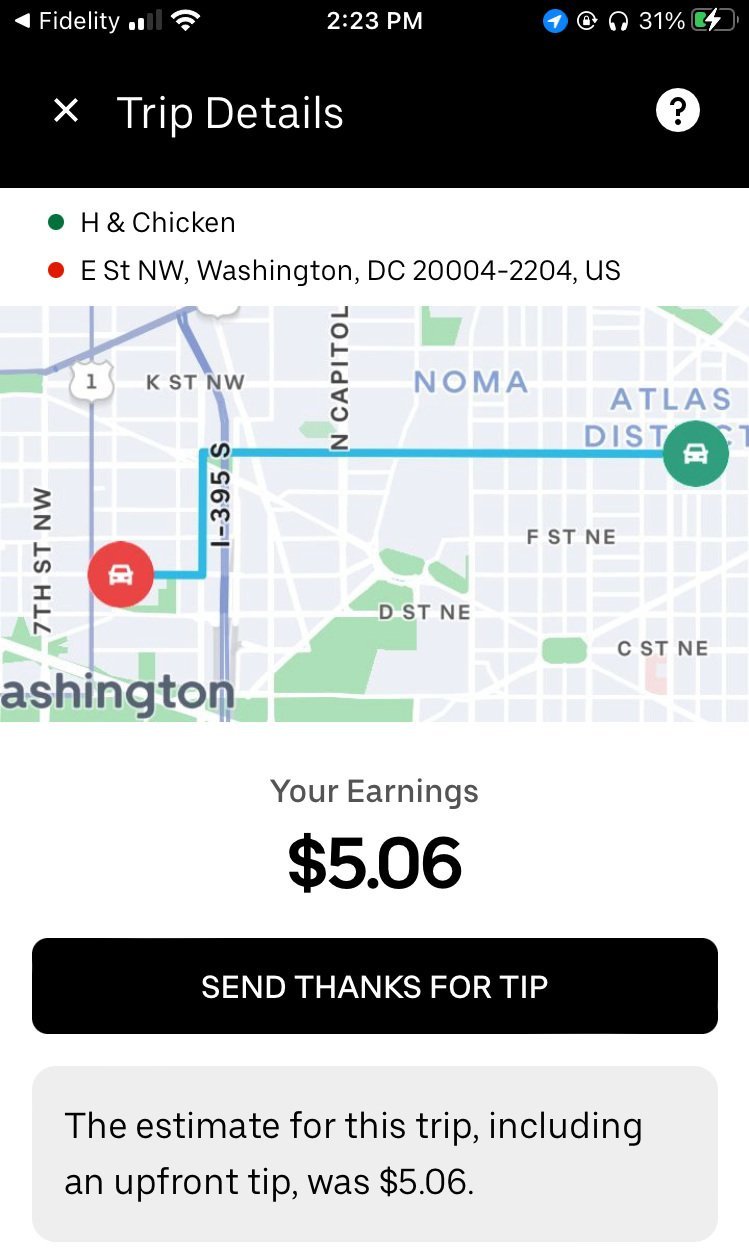

My only considerations were time and convenience. I wanted the smallest orders, from the most efficient restaurants, traveling the shortest distances. It ended up taking me 4 days to complete all 40 orders, with my shortest delivery being 0.2 miles and the majority falling under a mile.

My total earnings from the 40 trips was $179.17, or just $4.48 per order, so Uber Eats kicked in $80.83 more to meet the $260 guarantee (along with the $100 in quest pay). Note that the guarantee payment was only made an hour after my last delivery, once the tip for the last order was “finalized.” I spent a total of 12.62 hours working, for a total of $28.53 per hour.

Conclusion

Since no one knows how the delivery landscape is going to shake out over the next few years and which, if any, of the existing companies will survive, I am a strong believer in at least staying active enough on each of the platforms to keep your accounts from lapsing. Since the experience of working for each company is so different, it’s natural that you’ll be more or less motivated to work for one platform or another. Since DoorDash is my “main” platform, stackable guarantees and quests are a perfect opportunity for me to spend a few days working on Uber Eats, making plenty of money and keeping the account active for a rainy day.

Additionally, I believe from the wording on the e-mail I received that my guarantee was a direct result of my inactivity on Uber Eats — a nudge to come back to the platform. It did work (money has that effect on me), but if anything that motivates me to let the account go dormant for another month to see if I get another guarantee worth pursuing.